9-5-2009 United Kingdom:

9-5-2009 United Kingdom:

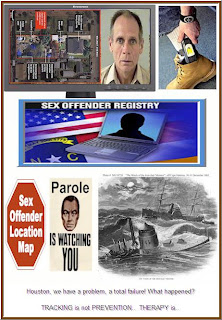

The Jaycee Dugard case illustrates how America's sex offender registries hurt efforts to stop repeat sex crimes

Americans have been doing some soul-searching about our approach to monitoring convicted sex offenders since the recent discovery of Jaycee Lee Dugard. Dugard was kidnapped in California at age 11 and held captive for 18 years in Phillip Garrido's garden. He managed to hide his secret prisoner from the police even though he was a convicted rapist and his name appeared on the public sex offender registry.

In the past, news of a horrific crime committed by a convicted sex offender inevitably led to widespread calls for increasing the scope of sex offender registration and community notification laws. Over the past 15 years, the US has expanded its registration and notification schemes to include an estimated 674,000 convicted sex offenders. Some remain on the public list for the rest of their lives, regardless of the seriousness of their offence, the current threat they might pose or their progress toward rehabilitation. The effectiveness of such laws has rarely been questioned, and they enjoy widespread public support.

But this time around, there has been a different type of discussion. Rather than just calling for tougher sex offender monitoring laws, Americans are openly wondering if a new approach is needed to deal with convicted sex offenders who have re-entered the community.

Although Garrido's case is extraordinary, it illustrates the flaws in America's sex offender registration and community notification schemes. Experts in sexual violence say that placing all convicted sex offenders on a registry for life may do more harm than good. The public nature of the registry makes it nearly impossible for convicted sex offenders to re-enter the community with the kind of support system they need to reduce their likelihood of committing another offence. Low-level offenders who pose little risk to the community are monitored in the same way as high-risk offenders, diluting police resources to concentrate on those, such as Garrido, who pose a high risk of committing another offence.

Furthermore, focusing so much public attention and resources on convicted sex offenders ignores the reality of sexual violence in the United States. It is estimated that 87% of new sex crimes every year are committed by individuals without a prior sex crime conviction. And very few sex crimes move through the system – less than one-third of all reported rapes result in an arrest.

So pouring scarce resources into monitoring all convicted offenders means there is less money for programmes to prevent sexual violence and counsel victims and for the rape investigation units, rape evidence testing and other tools that could bring justice in these cases.

Because of such concerns, Human Rights Watch called in a 2007 report for a major revamping of America's sex offender laws. Registration should be limited to former offenders who have been individually assessed as dangerous, and only for as long as they pose a significant risk. Community notification should be restricted to those who genuinely can benefit from knowledge about dangerous former offenders in their midst.

Sex offender registration and community notification laws didn't cause Garrido's crimes, but they didn't help the police stop them, either. While Americans are starting to question the value of our extensive sex offender monitoring system, it remains to be seen whether these doubts will lead to real reform.

Once sex offender laws are in place, it is hard for politicians to repeal them, because they don't want to appear weak on the issue of sex offenders. If Britain wants to do more to prevent sexual violence, it should keep its sex offender registry narrowly focused, and use the savings in time, energy and resources to implement sexual violence prevention policies that will actually keep the public safe. ..Source.. by Sarah Tofte

September 5, 2009

Sarah Tofte: America's flawed sex offender laws

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment